-

America's current grading system is failing students, higher education institutions and employers

Currently, assessments of student learning are reported with a combination of letter grades, standardized test scores and time spent in the classroom as often recorded on a student transcript. Transcripts detail a student’s time spent in classrooms, but do not truly capture the depth and breadth of a student’s learning or communicate precisely what they have learned.

There are four fundamental weaknesses of this approach that must be addressed to better measure, record, and report on student competencies based on what they have learned, instead of based just on time spent in a classroom. Specifically, it:

Is rooted in a problematic theory of learning: Transcripts based on credit hours (or Carnegie Units—120 hours of interaction with an instructor in a yearlong class) suggest that the most important element of learning is the amount of time a student spends interacting with professional educators. While the Carnegie Unit has become the primary indicator of student development, that approach lacks roots in any meaningful theory of learning. As a result, many educators avoid powerful instructional activities, such as peer and/or independent project-based work, that may not count toward Carnegie Unit completion.

Lacks transparency: The Carnegie Unit also fails to provide information on the quality of learning. For example, one hour of a stimulating and challenging learning environment will support deeper learning than one hour spent completing superficial worksheets, yet both will count equally toward a Carnegie Unit. This makes it more difficult for caretakers, teachers, college decision-makers and/or employers to meaningfully distinguish applicants’ true learning.

Does not recognize out-of-school learning or interdisciplinary competencies: Transcripts do not consider the competencies students learn outside of schools or in interdisciplinary learning experiences. For example, online courses, apprenticeships, internships, or even learning as part of social networks are not reflected on transcripts. Further, Carnegie Units require the division of curricula by subject matter, suggesting that a student's learning in a STEM course is completely unrelated to their ELA learning. This narrow focus means that important skills, such as critical thinking and collaboration that cross subject areas, go unmeasured and unreported.

Assumes all students learn at the same rate: In order to meet the minimum time required for a Carnegie Unit, students must keep pace with a set learning sequence. This does not allow for the creation of flexible learning pathways to support individualized learning styles. Students not able to keep pace will find themselves held back and separated from their peers, creating an inequitable learning environment that delays academic progress.

-

Next-Generation Badging

Our next-generation badging approach gleans insights from an influential initiative launched by the MacArthur and Mozilla foundations in 2012, as well as more recent badging strategies, related research and lessons learned from the past decade.

Our strategy differs from prior efforts in three key ways:

First, we anchor our strategy in a competency-based approach to education in which units of learning are understood in terms of real-world capacities, rather than the traditional Carnegie Unit based on seat time in a typical year-long course.

Second, we address the persistent need for different levels of assessment information (e.g., formative and summative) by introducing three coherently linked levels of badges (micro, meso, and macro) to meet the needs of learners, educators, and other stakeholders at all stages of learning.

Third, we directly confront the lack of credibility and comparability that has hindered prior badging efforts by proposing an infrastructure to validate badges.

The first two innovations have been proposed before, but we believe our proposal is the first to bring them together in combination with the validation infrastructure needed to ensure the badges have value to all stakeholders.

To support the valid use of badges, we propose a three-tiered, competency-based strategy that honors stakeholder expertise and local priorities, while giving more flexibility to learners and setting shared standards of evidence for competencies at different stages of learning.

Microbadges can be awarded based on locally developed teaching strategies to recognize small achievements, prompt reflection and spark motivation by allowing both teachers and learners to gauge progress toward higher-level competencies. For example, a student in an 8th grade civics class might earn a microbadge by doing a brief research project on a historical figure or group that used civic engagement to bring about change.

Mesobadges would be associated with a specific competency based on criteria established by an independent standard-setting body (e.g., a State Department of Education, disciplinary professional association or commission charged with such a task); assessments created to measure acquisition of these competencies would be reviewed and validated by an independent expert body to allow for flexibility and innovation, while also ensuring credibility and transferability across education providers, employers, etc. For example, over the course of an 8th grade civics class, a student might earn a mesobadge by demonstrating age-appropriate competency in civic participation. To earn this badge, they might submit a microbadge for studying historical civic engagement (see example above) in addition to other microbadges related to other elements of the competency (e.g. a media literacy microbadge).

Macrobadges will allow educators and learners to “package” mesobadges into a badging portfolio that documents specific learning pathways and demonstrates complex and connected competencies. This badging portfolio could replace or supplement the transcript, credit hours or GPA as a broad summary of a student’s development. For example, a civics macrobadge could be awarded when a student earns a set of mesobadges associated with competencies, such as civic participation, aligned with each of the seven themes of the Roadmap to Educating for American Democracy, guidance and an inquiry framework states, districts and educators can use to offer high quality civic and history learning opportunities.

We envision an open education resource (OER) approach to ensure that educators, schools and students across the country can equitably participate in this competency-based approach to documenting student learning and achievement. The OER would include:

Tools and resources to support the development of assessment instruments appropriate for each badging tier, and a centralized review process for approving new meso- and macro-badges.

Online access to the assessment instruments supporting meso- and macro-badges, as well as to documentation of the evidence base for their validation by the Badging Board.

Digital tools to support educators in awarding badges, learner collection and ownership of badges, and employer and admissions officer viewing of badges.

-

Badging Supports Comprehensive Assessment of Student Learning

Personalized learning is the path forward for uniting excellence and equity in education. A competency-based badging approach better and more fully assesses students’ individual progress and achievement of integrated knowledge, attitudes, values, skills and behaviors. In contrast to the traditional assessment system, a badging approach is based on a more comprehensive evaluation of what students actually know and can do.

Badging provides:

A more inclusive approach to measure a student’s individual learning. Badging allows both traditional and nontraditional students to demonstrate skills and knowledge gained from school electives, extracurricular activities, training programs, and work experience. This provides those who have taken a nontraditional path to education a viable path to demonstrate their competencies.

A more robust understanding of what students can do. Letter grades are low-information indicators of student learning. Two students with A’s in the same class may or may not indicate equally sophisticated work. For a student to earn a badge, their teacher or supervisor must detail evidence of how they were earned.

Flexibility to document incremental progress and target interventions. Letter grades apply an all-or-nothing approach, meaning a student must master all necessary skill sets and knowledge to earn credit for the course. Badging benefits both students and teachers. A student can demonstrate incremental progress by earning a badge in one skill, even if they have yet to master another. This provides for a more authentic educational experience and can motivate students to continue learning. Badging can also help a teacher or supervisor target interventions for learners where and when needed.

FACTSHEET

A Call to More Equitable Learning:

How Next-Generation Badging Improves Education for All

To truly assess a student’s readiness to advance in college and/or career, the American education system must evolve to measure, record and report every student’s mastery of well-defined core competencies, including both subject-matter content knowledge and other competencies, such as critical thinking, collaboration and communications.

A strategy of assessing K-12 student learning based on badging of explicitly stated competencies will provide colleges and employers with a clearer and more complete picture of a student’s knowledge, skills and preparation.

Levels for Measuring, Recording, and Reporting Student Learning

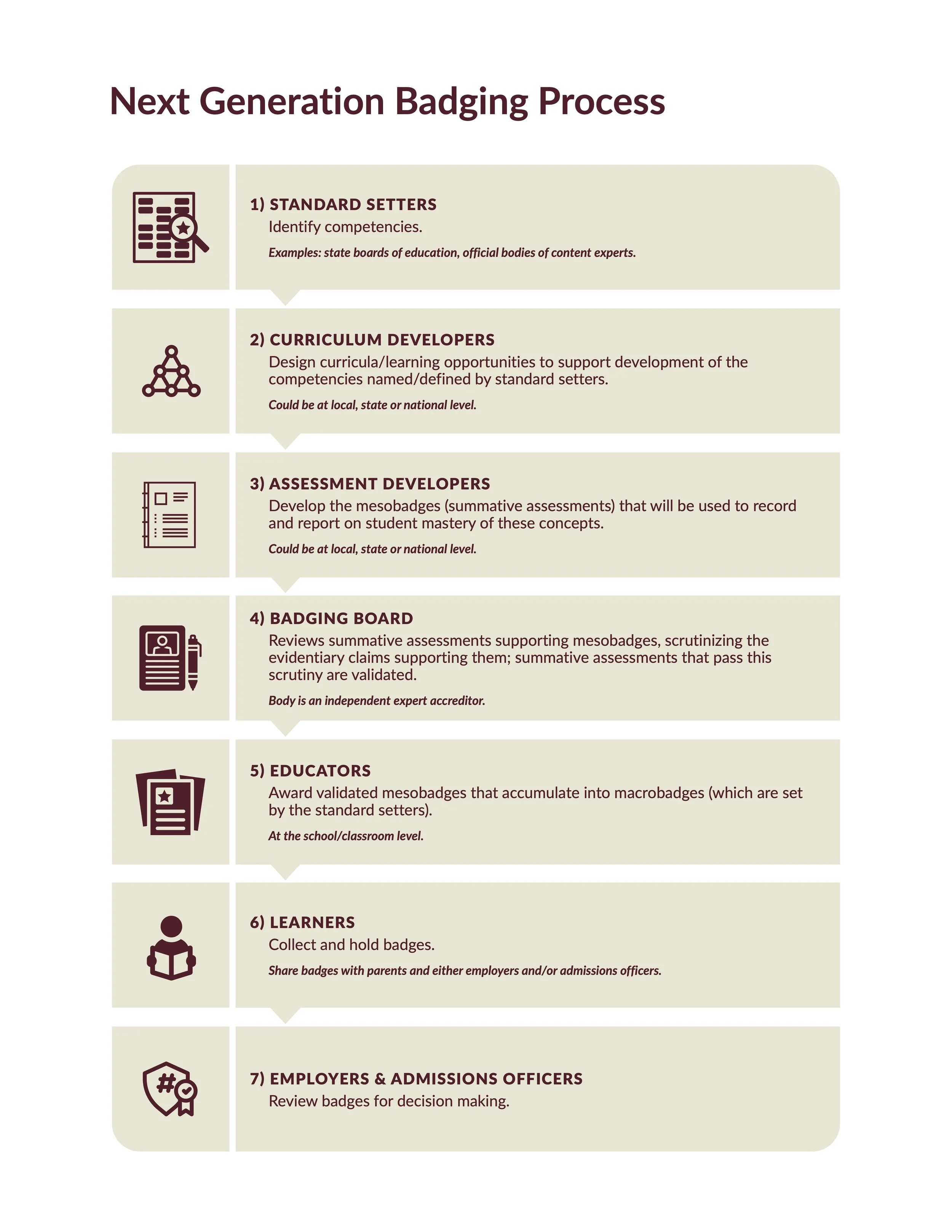

Next Generation Badging Process